On Wednesday, May 25, 2016, RG, my hiking partner, and I fell half way down an icy mountain and almost died. We want to thank Custer County Search and Rescue, EMS and Pueblo Park View Hospital for taking care of us.

On Wednesday, May 25, 2016, RG, my hiking partner, and I fell half way down an icy mountain and almost died. We want to thank Custer County Search and Rescue, EMS and Pueblo Park View Hospital for taking care of us.

Preface

In the Colorado Rocky Mountains, there are 58 mountains with peaks over 14,000 feet. They are commonly referred to as ‘14’ers.’ RG and I went to Colorado to climb several of them as part of our training for Canada’s 100K Ultra Trail du Mont Albert ultra-marathon in June.

I’ve climbed mountains and backpacked all over the world; the Andes, Himalaya, Alps and summited Mt. Kilimanjaro (19,340 ft.) in Africa. While Humboldt Peak in Colorado would be my 14th, 14’er, it would only be RG’s 2nd. His first, achieved only two days earlier, Pikes Peak (14,110 ft.).

Accidents happen, but this one could have been avoided had I not broken one of the cardinal rules of mountain climbing. I knew better and that bad decision led to a terrifying chain of events that almost got us killed.

Humboldt Peak

It was a beautiful, clear morning in the 40’s F, when we started hiking the South Colony Trail to climb Colorado 14’er, Humboldt Peak (14,064). In the Sangre de Cristo Wilderness, the mountain is located a little more than 3 hours southwest of Denver, near the small town of Westcliffe, CO.

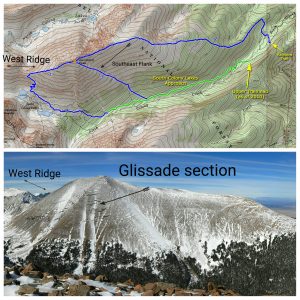

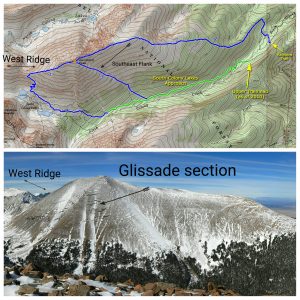

Our objective was to take the South Colony Trail approach, starting at 9,950 feet, to the West Ridge and hike to the summit of Humboldt Peak. A simple, 11-miles round trip, Class 2 hike, with 4,200 feet in elevation gains, estimated to take between 6-8 hours. Even in snowshoes.

Research

I read maps, multiple summit reports, checked the weather, talked with a ranger and a group of guys who had summited the day before. They confirmed, that given the approach was mostly covered in deep snow, it would take between 6-8 hours round trip, snowshoes were needed, extra layers, and it was probably best to follow footprints as snow had covered most trail markers.

Equipment/ Backpacks

We each used Leki trekking poles and carried day backpacks (his a CamelBak Fourteener and mine, a Thule Stir 35) with water, snacks including TME Bars and Honey Stinger Gels, Yaktrax (removable spikes/traction for shoes), MSR snowshoes, extra layers and a few emergency supplies like a knife, Bic lighter and for me, a headlamp, signal mirror, a few hand warmers, hexamine fuels cells and Chapstick (lip protection and a fire accelerant). I also had my cell phone and a spare battery charger for it. RG’s cell phone couldn’t get a signal in the wilderness so we left it in the SUV (he has Sprint, I have Verizon).

This was only a day hike so I left a few emergency/survival items behind that I would normally carry on a multi-day trip.

What Went Wrong…a Few Things

#1. We started late. We camped by the South Colony Trailhead and by the time we crawled out of our sleeping bags, eat breakfast and hit the trail, it was 10am. I wasn’t overly concerned because the forecast was excellent and it was only a 6-8 hour hike. We’d make it back in plenty of time before sunset, around 8pm.

A rule of thumb with 14’ers advises climbers to be up and off the summit by noon. Colorado tends to have scattered afternoon thunderstorms. However, we had blue skies and no thunderstorms were in the forecast.

#2. We put on snowshoes within a mile of the start. Two miles in, we saw the last trail sign and had to follow footprints in the snow. Unfortunately, these prints took us on an indirect, winding, ‘scenic route,’ that skirted around the mountain and through the San Isabel Forest. It cost us an hour or more of time and we still had not made it to the West Ridge. But we could see it.

#3. The shortest distance between two points is a straight line. To make up time, I decided we’d start climbing the mountain from where we were and intersect with the West Ridge route on the ascent. This would make it a more difficult Class 3 climb, steeper, requiring scrambling or un-roped climbing over large rocks. I love this type of climbing and RG said he liked scrambling and was up for it. We strapped the snowshoes back onto our packs and began our ascent.

I worked my way up the mountain keeping RG in sight. He did fine, at first, but the higher and steeper we went, the slower he moved. He was not sure footed on this terrain and incline. He didn’t have the experience. The altitude and 60 mph wind gusts didn’t help either. I was a little concerned, but the only way he was ever going to learn to climb mountains was from experience. I wanted to give him it.

#4. I pushed the turnaround time to 3:00pm. Something I’d never done before. I had anticipated being up and off the summit by then, and would have, but not with RG. He really wanted to summit, and I wanted to summit with him, so I made the exception.

I rationalized that once we made it to the top, we’d traverse and descend a different way, down the Southeast Flank Gully. Thus, skipping most of the forest and putting us back on the South Colony Trail within a mile or two of the trailhead.

Plus, this route was mostly snow covered, we could glissade (a controlled slide on your butt in the snow) most of it and save a lot of time down climbing.

#5. Unfortunately, we didn’t summit until 6pm. STUPID! CRAZY LATE. I know.

I had broken the cardinal rule of mountain climbing, ‘sticking to a turnaround time.’ Now it was going to bite us on the ass. And it would. Literally.

Ready to get down, we traversed to the Southeast Flank route and prepared to glissade. We put on waterproof pants (on top of the other three layers of pants we wore, including compression tights ) sat on our butts and pushed off. Using our trekking poles and shoes we controlled the slide in the snow.

Falling off a Mountain

We took turns glissading, one after the other, making our way down in short slides. It was quick and fun…for the first thousand or so feet.

Then, it wasn’t.

Taking his next turn, RG pushed off before me. Ten feet into his glissade, I watched his slide turn into a terrifying, uncontrollable head over feet tumble. The snow had turned to ice. Wearing a blue coat and black pants, he flipped over and over, careening down the mountain. Water bottles and snowshoes flew off his pack and his trekking pole went flying. RG slammed into a rock ledge, bounced off and onto another before sliding to a stop. A crumpled heap of black and blue. Unmoving.

I looked down the mountain searching for movement. Was he breathing? Could he move? ‘Oh my God, oh my God,’ I thought. I yelled, “RG!! RG!!”

And, slowly, but surely, he sat up. ‘Thank you, Jesus!’

He was in a daze. I told him to stay put. ‘Don’t move!’ I shouted. ‘I’m going to come down very carefully.’

At least, that was the plan.

I dug my hiking shoes’ heels into the snow and scooted down. Slowly. Things were steady and then I hit ice, slipped and started sliding.

FAST.

I couldn’t stop. I desperately kicked my feet and dug the trekking poles into the ice to gain purchase. Nothing. I bounced off the first rock ledge and then the second. I lost the trekking poles and water bottles, flipped onto my stomach and kept sliding. In vain, I scratched and clawed into the frozen snow with gloved fingers. I was cascading towards a deadly rock cliff and couldn’t stop. As I slid past RG, in an effort to stop me, he grabbed ahold of my backpack’s hip-belt. It ripped off in his hands. The force flipped me onto my back, and slowed me down, just enough, to slam my right foot through the icy crust and onto a large rock. I came to a halt.

Breathing heavily, ice crystals clinging to my face, I gazed over my toes at the rock that stopped the out of control slide. It was two feet from the cliff’s edge.

Heart pounding, adrenaline pumping, my mind screamed, ‘Holy Shit! Payge you are an IDIOT!’

I gingerly sat up, keeping that right foot firm on the rock. After a quick body assessment, I was surprised to find that nothing really hurt, except for the right shoulder. It hurt bad.

We had fallen, slid, tumbled, careened, whatever you want to call it, several hundred feet down the mountain.

We still had a couple thousand, steep, feet to descend and I knew we couldn’t do it on this ice. We didn’t have the right equipment (ice axe, crampons). I surveyed the immediate area, desperate to get away from the cliff’s edge and get us down the rest of the mountain. Five feet to my left was a rocky, boulder outcrop, untouched by snow.

Looking back, RG, twenty feet above me, I shouted and pointed, “We have to get off this ice. Scoot to the rocks, meet me around this boulder and we’ll down-climb the rest of the way.” He nodded.

Gingerly, I pulled off my backpack, clamped on the snowshoes, and put the pack back on. I hoped the spikes and teeth would hold me on the ice while I inched towards the rocks on my butt. If I slipped, I was dead.

The snowshoes did the job.

With the wind hallowing, I watched RG make it to the rocks and disappear behind a large boulder, the size of a house. He was supposed to go to the other side and come down to me. I waited. And waited. I yelled up to him, but there was no way he’d hear anything over the wind. Where was he? Was he hurt? Did he slip and fall and was now unconscious?

With my right shoulder damaged, I couldn’t climb up to help him. I looked at my watch, it was 7:20pm and the sun was dropping behind the mountains.

911

My fingers, frozen and numb from clawing at the ice, managed to unzip my waterproof jacket, reached into the pocket of my second coat, a down jacket, and grabbed my cell phone. Thank God I had put it there. It was undamaged. I called 911.

Never in a million years did I think I’d have to make a call like the one I did that night.

The 911 operator was calm and listened. I described what happened and where I was located. She put me in touch with the Custer County Search and Rescue, Captain, Cindy Howard.

Cindy asked me detailed questions. What were we wearing? What was in our packs? Gear? Climbing experience? She said it was too late for a helicopter and they would have to try to find us on foot. I told her my plan was to down-climb and make a fire at the edge of the forest and gully boulder field. It would be dark soon. RG, if he was ok, would know where to go. She agreed, said she’d get her team assembled and to keep in touch.

This mountain was steep. It took more than an hour to descend over rocks, fallen trees and snow. It was almost dark by the time I reached the boulder field. I thanked my lucky stars that I had packed that headlamp.

In the distance, near the gully and on the boulders, I saw a shadow. Then I heard,

“HELP! HELP! Please don’t go away!!” It was RG. He had somehow descended and was staggering over rocks towards the only light around, my headlamp. I called to him. We stumbled towards each other and collapsed into each other’s arms. He was shaking and in a lot of pain. Everything hurt. He had hit his head and it was hard for him to breathe.

I asked him what happened up on the mountain, after he reached the outcropping of rocks. RG said they were slick with ice and it took him awhile to find a better route. He had to carefully up-climb before descending.

I called Cindy and told her I had found RG.

Normally, when someone is lost it is advised they stay in one place. It makes it easier for Search and Rescue to find them.

However, Cindy said if we could walk, we needed to get off the boulder field and make our way down the trail. Due to the snow and dense forest, their Artic Cat could only go so far. If her people were going to find us that night, it would be on foot. In the meantime, they’d try to ping my cell phone.

Survival

We were hurt, cold, tired and thirsty, but over the next couple hours, RG and I post holed through deep snow, sometimes sinking up to our thighs. We followed tracks, hoping they led to the main trail.

By midnight, we had descended to 10,200 feet. The wind had stopped and the temperature, above freezing. Near the main trail and exhausted, we decided to take a break by a stream and hydrate. I used a Bic lighter and a hexamine fuel cell to start a small fire with twigs and branches.

Given our layers of clothing, I felt we’d survive the night if they did not find us. It would be miserably cold, but we’d survive. I had some hand warmers, another pair of warm pants, a long-sleeve shirt in my backpack and a sarong we could use as a blanket or tarp. I was kicking myself for not having an emergency blanket or bivy and several other items I regularly keep in my pack for multi-day trips. Including a whistle. Ugh!! Another lesson learned.

Search and Rescue

No more then 15 minutes after finding the stream, I heard a faint whistle. “Shhhhh,” I said to RG, “I hear something.” It came again. “HELLO!!!” I yelled. “OVER HERE!! OVER HERE!” We screamed, waved the beam of the headlamp and tried to make our little fire bigger. Brighter.

Wearing huge backpacks and boots, two rugged, mountain angels appeared through the pine trees. With a warm smile, they said, “How you guys doing?”

Over the next hour and a half, they administered first aid to RG. They gave him warm socks, wrapped his feet in an emergency blanket and put a sleeping bag over him. They built a bigger fire and gave us Gatorade and snacks. We waited for two other Search and Rescuers to join us. They brought snowshoes, for RG to wear, so we could better hike the last mile out to reach the Arctic Cat.

I apologized profusely for getting us into this predicament. RG said it was his fault, he had moved too slowly. It didn’t matter. I was the more experienced hiker and climber and should have turned us around. It was embarrassing and I knew better. SARs said not to worry. These things happen and that more experienced climbers have been hurt or died in these mountains for a number of reasons. They were kind and understanding.

Safe

Safe

It was 4am when we made it out of the wilderness and onto an ambulance. The nearest hospital was an hour a way in Pueblo, CO.

When I knew we were safe, the adrenaline wore off and my whole body began to ache. My shoulder screamed in pain. All I wanted to do was go to sleep.

Injuries

Injuries

The fall had literally bit us on the ass. Ice shredded through three layers of pants. Our forth layer, compression pants, were blessedly untouched. We had some nice bruises though.

The doctors and nurses examined, x-rayed and cleaned us up. RG suffered a mild concussion and bruised ribs. We both had lacerations and abrasions on our legs and arms. I also had them on my back, stomach, face, lip and black eye. As for my right shoulder, I had completely torn my rotator cuff, fracturing and tearing off part of the humerus (the long bone in the upper arm). Surgery and months of rehab were in my future.

Lessons Learned

We are lucky to be alive. Accidents happen but this one could have been avoided. I (we) have learned some valuable lessons.

- Keep the turnaround time. NO exceptions. – Do what you know is right.

- Even on day hikes, each person carries a fully supplied emergency kit in their pack

- Carry a stainless steel water bottle in your pack

- Have a GPS or download compass app on your phone.

- Never glissade without an ice axe.

Always let someone know where you are going and when you expect to be back. Instruct them to find you if they do not hear from you by a certain time.

Leave a note in your vehicle with the same information and an emergency contact.

Emergency Kit

Below are the top 12 items I will be sure to keep in my day and multi-day packs.

- Knife

- Fire (both a Bic lighter and Ferro rod)

- Survival blanket or bivy

- Whistle

- Headlamp w/ extra batteries

- Cell phone w/ spare battery charger

- Extra layers, Sarong

- Paracord

- GPS/Compass

- Stainless Steel Water Bottle

- Duct Tape

- Cargo Needle

There are many items you could add to this list. Much depends on the environment, your comfort level and how much you want to carry.

Survival expert, Dave Canterbury, has a list everyone should review, called the 10’s C’s of Survival.

If you want a great pre-made kit to get you going, check out, Adventure Medial Kits.

Under water-proof pants, I wore C2’s Performance Tights on the snowshoe ascent from Barr Camp to summit Pikes Peak, 6.5-miles and an almost 4,000 foot climb. It was 28F, but the wind chill dropped temperatures down 11F. Thanks to the flexible Polartec® power stretch construction, I stayed warm, dry and retained the agility needed to climb up and over steep snow banks.

Under water-proof pants, I wore C2’s Performance Tights on the snowshoe ascent from Barr Camp to summit Pikes Peak, 6.5-miles and an almost 4,000 foot climb. It was 28F, but the wind chill dropped temperatures down 11F. Thanks to the flexible Polartec® power stretch construction, I stayed warm, dry and retained the agility needed to climb up and over steep snow banks.